Ad Code

Myths and Legends

Unknown

10:17 AM

Myths and Legends

A land of fantasy and imagination

Vietnam has an enormous treasury of myths and legends, both ancient and recent. As the language developed, it often used poetic imagery to describe and narrate through metaphor and allegory. The country’s strong animist tradition produced a wealth of anthropomorphic symbols.

Where legends don’t exist, the Vietnamese feel an urge to invent them. In the caves of Ha Long Bay, for example, local guides narrate many ‘legends’ related to stalagmites and stalactites that vaguely resemble animals or people. Charming and imaginative they may be, but nearly all have been composed in the last decade.

The legend of the Lake

Other legends have a more respectable record. The name of Hanoi’s Hoan Kiem Lake means ‘Lake of the Returned Sword’, a reference to a local legend. It is said that Le Loi, who became the great Emperor Le Thai To, was awarded a magical sword by the spirit of the Lake to help him drive invaders from the land.

Years later, after victory, he sailed out on the Lake to express his gratitude by making a sacrifice to the spirit. Suddenly, a giant turtle appeared and the sword flew from the Emperor’s scabbard. The turtle seized the sword in its mouth and plunged to the depths to return the sword to its rightful owner. Even today, people believe that the lake is inhabited by large turtles, and periodic sightings are claimed as omens of good luck.

A Vietnamese creation myth

An ancient Vietnamese creation myth abounds with animist symbolism. Lac Long Quan, the son of a mountain god and a water dragon, was given the land of Lac Viet by his parents. He built two palaces, one in the mountains and one in the ocean. Later he fell in love with a beautiful fairy, Au Co, and transformed himself into a handsome young man to win her over. They married, and a year later, she laid a hundred eggs that hatched into human babies that quickly matured into adults.

Unfortunately, Lac Long Quan remained in his water palace while Au Co lived on land. She became lonely and pined for her homeland, so much so that she took her hundred children to visit it. It became obvious that the couple should separate. They agreed that half the children would go with their father to the land next to the ocean, and the others would follow their mother to the mountains, thus creating the Vietnamese race – the dragon and the fairy’s grandchildren.

Sentiment and emotion

Mythology is also prevalent in European countries. There, however, myths tend to be built on specific events, and often have a Judeo-Christian moralistic element – pride coming before a fall, the weak overcoming the strong through virtue and purity, and goodness appearing in disguise to test the virtue of humans, being common themes. Similar themes appear in Vietnamese myths, but a far greater emphasis is placed upon sentiment. Star-crossed lovers are very popular myths, often ending in unrequited love and tragic death, in a context of arranged marriages.

Closeness to the spirit world

In European mythology, the ‘Gods’ are usually powerful figures who sit in judgement or intervene in human affairs from a distance, and evil often comes in distorted human form (ogres, trolls, goblins, and so on). In Vietnamese mythology, spirits and ‘fairies’ are everywhere and are much closer, often living among human beings. The concept of ‘evil’ is unclear – the human characters are usually the authors of their own misfortunes. Domestic issues are quite common in folk stories: hardworking husbands and lazy wives, false friendship and virtue rewarded, for example.

‘Urban’ myths and cautionary tales

There is also a strong tradition of folk fables where the protagonists are the common people and authority represented by the local mandarin – the theme is often a variation of the native wit of the peasant overcoming the erudition and pomposity of the mandarin.

An old anonymous collection of cautionary tales akin to Aesop’s fables may have originally been moral lessons for young children to teach them the principles of correct Confucian behaviour.

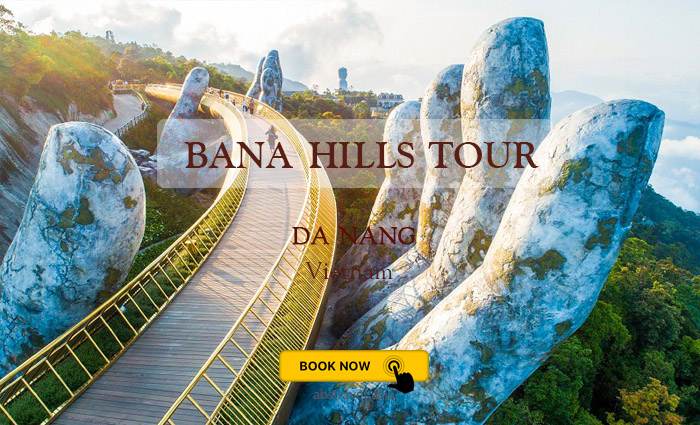

Best Package Tour Danang – Hoian – Ba Na Hills 4D/3N

Price from: US$180

Package Tour Hanoi – Halong Bay – Sapa 5D/4N

Price from: US$265

Bài viết phổ biến

Subscribe Us

Categories

- ABOUT VIETNAM (195)

- CULTURE - TRADITION (88)

- FESTIVAL VIETNAM (3)

- HOI AN TOWN (1)

- HUE CITY (5)

- MUI NE BEACH (1)

- NEWS - HIGHLIGHTS (11)

- OUR SERVICES (8)

- PHONG NHA - KE BANG NATIONAL PARK (1)

- QUANG BINH PROVINCE (1)

- SAPA (1)

- TOURIST ATTRACTIONS (81)

- USEFUL INFORMATION (13)

- VIETNAM FOOD (18)

- VIETNAM PHOTOS (17)

0 Comments